The power is in the people and politics we address

Tupac Amaru Shakur

The power is in the people and politics we address

Hampton Roads is a region of Virginia in the South Eastern United States that includes seven cities that are all under threat from rising sea levels. Norfolk is in Hampton Roads, is sinking, and is in imminent danger of experiencing a preventable climate disaster. Should a Katrina-like hurricane strike the region, there is potential for a devastating climate crisis-driven water event. That would negatively impact primarily Black communities such as St. Paul’s, a district of Norfolk, and destroy lives, cultures, homes, and communities. The heaviness of the omnipresent threats and impacts of the climate crisis can sometimes drown out the beautiful resistance that organizations and communities are engaged in as they fight for climate justice through community organizing. This research project explores Hip Hop Caucus’ Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project. Through centering the perspectives and voices of organizers, community members, creatives, and artists, this project explores and uplifts the creative and organizing processes, goals, wisdom, and lessons learned. Whenever there is injustice, including climate injustice, those most deeply impacted by centuries of exploitation, oppression, and white supremacy are using the power of community and cultures to shift an unjust and destructive world paradigm into one that is just and equitable; one that serves, protects, and uplifts the people and the futures of our collective children.

In August 2019, Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) began a three-year organizing project in Hampton Roads known as the Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project (HROP). HHC is a non-profit and non-partisan organization that connects the hip hop community with civic processes through advocacy and creative and cultural organizing. Using creative and cultural organizing strategies and driven by a belief that preventing a climate disaster in the Hampton Roads region is crucial, HHC engaged with various stakeholders to help build movement, shift cultures, and expand community power in connection with climate justice and voter mobilization. This research explores the HROP, including the organizing and creative processes in the project, comedy shows on the climate crisis, and two films that have grown out of the project. Although the scope of this research project is from July 2019 to December 2020, the HROP is ongoing and continues to include filmmaking as a component of the project.

This research project was conducted over six months and used a qualitative research design in the form of a case study. Data was collected through internal HHC documents and interviews with nine people involved with the HROP. The data was then analyzed through an abbreviated form of thematic analysis. The findings are presented in this public format in an intentionally more informal manner to help educate and engage as many communities, community organizers, organizations, creatives, and artists as possible.

Hyperlinks are woven throughout the presentation to center the voices of those interviewed. The recordings are from participant interviews, and their use allows readers to listen to participants speak for themselves as part of the story. There are also links to explore documents and contextual information. Additionally, the timeline in this presentation is interactive. Using it allows for a more granular exploration of the HROP phases—the creative and organizing processes within the project, the phase goals, and stakeholders. Uplifting people and voices of the community, organizers, artists, and creatives of color involved in this organizing project is a mandatory component of centering the Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities who are often disproportionately impacted by the climate crisis.

Kusnetz, Nicholas. “Sea Level Rise Is Creeping into Coastal Cities. Saving Them Won’t Be Cheap.” Inside Climate News, Inside Climate News, 30 Nov. 2020, https://insideclimatenews.org/news/28122017/sea-level-rise-coastal-cities-flooding-2017-year-review-miami-norfolk-seawall-cost/.

Fears, Darryl. “Built on Sinking Ground, Norfolk Tries to Hold Back Tide amid Sea-Level Rise.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 17 June 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/built-on-sinking-ground-norfolk-tries-to-hold-back-tide-amid-sea-level-rise/2012/06/17/gJQADUsxjV_story.html

Three research questions guided this project:

What are the creative and organizing processes designed and implemented as part of the Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project?

How have these processes contributed to building movement, shifting cultures, and expanding community power?

What lessons and wisdom do this organizing project provide for other practitioners, community organizers, creatives, and artists who want to use creative and cultural organizing strategies connected with visual storytelling through films to pursue climate justice?

HHC seeks to share the processes, experiences, wisdom, and “grows” and “glows” of this ongoing organizing project with those working for climate justice through creative and cultural organizing. HHC believes in creating and sharing knowledge and cultures that serve collective futures. The author hopes the wisdom and lessons found here will help others use creative and cultural organizing strategies to help cultivate the power of the people, shift cultures, and foster the re-imagining of the narratives on which communities and what solutions should be centered within the movement for climate justice.

To more effectively communicate, think of hip hop ciphers in which raising energy and making connections is made possible through shared slang and cultures. Four terms are necessary for this presentation cipher: cultures, processes, building movement, and creative and cultural organizing. Cultures shall be defined as multi-dimensional, fluid, shared, yet, not necessarily mutually exclusive sets of understandings, beliefs, and processes that allow for unlimited forms of communication. Interviewees for this project describe cultures with such words as “mode[s] of communication,” “unifying status,” “the way we love, the way we express ourselves,” and “as the strength of who we are.” Processes are defined as non-static pathways, actions, human interactions, and strategies designed and implemented to pursue and achieve identified goals. The discussion of processes in this presentation includes them as organizing processes and creative processes.

The terms cultural strategies and cultural organizing are accepted as necessary for shared understanding within the climate movement. However, Liz Havstad, Executive Director of Hip Hop Caucus (HHC), and Terence “TC” Muhammad, the Community Outreach Manager at HHC, hold the position that all “proper” organizing is cultural. Thus, when organizing is mentioned within this presentation, it always includes culture. The phrase build(ing) movement includes creating spaces where conversations around the climate crisis in Black communities and the solutions necessary to achieve climate justice are centered within the cultural contexts of the people and communities who are part of organizing. Additionally, the phrase creative and cultural organizing is being operationalized to be dynamic collections of creative and cultural organizing processes used to affect change informed by the lives, cultures, and needs of the communities being served in connection with cultural practices or tools in the form of the arts.

Osborne, Meredith. “Making Waves: A Guide to Cultural Strategy.” Revolutions Per Minute, Jan. 2014, http://theculturegroup.org/2013/08/31/making-waves/.

Sen, Nayantara. Power California, 2019, Cultural Strategy: An Introduction and Primer. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59d51916b1ffb6653bc0d058/t/5d702d973252f800016f1d6a/1567632808821/PowerCA-Cultural+Strategy+Primer-02+Digital.pdf.

Sen, Nayantara. Power California, 2019, Until We Are All Free: A Case Study. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59d51916b1ffb6653bc0d058/t/5d702fd21845f30001707396/1567633386385/Power_CA-Case_Study-A_websept.pdf.

“What Is Cultural Organizing?” Cultural Organizing, Cultural Organizing, 12 Aug. 2015, https://culturalorganizing.org/what-is-cultural-organizing/.

They just want us to wash away and get rid of us. And then once they get rid of us, they're going to develop it.

In solidarity with Indigenous Peoples worldwide, Hip Hop Caucus as an organization actively disrupts narratives woven together by white supremacy by upholding the value of stories, communities, and people in such a way that they do not begin with the devastation set in motion by colonial ideology and practices. Thirty-five million years ago, what is known as the Chesapeake Bay Bolide (a comet) collided into the location on Earth currently called Virginia and left a massive crater around the place we call Norfolk, creating the deep waters surrounding the region today. This event contributed to a rich and plentiful system of waterways that supports the Powhatan Peoples on their lands. Powhatan Peoples and their cultures and traditions continue and should be spoken of in the present.

Shirley, Jolene S. “The Chesapeake Bay Bolide Impact: A New View of Coastal Plain Evolution.” The Chesapeake Bay Bolide Impact: A New View of Coastal Plain Evolution – USGS Fact Sheet 049-98, USGS, 2016, https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs49-98/.

Long, Rebecca. “The Original Inhabitants of Our Land.” Chesapeake Bay Foundation, 12 Oct. 2020, https://www.cbf.org/blogs/save-the-bay/2020/10/the-original-inhabitants-of-our-land.html.

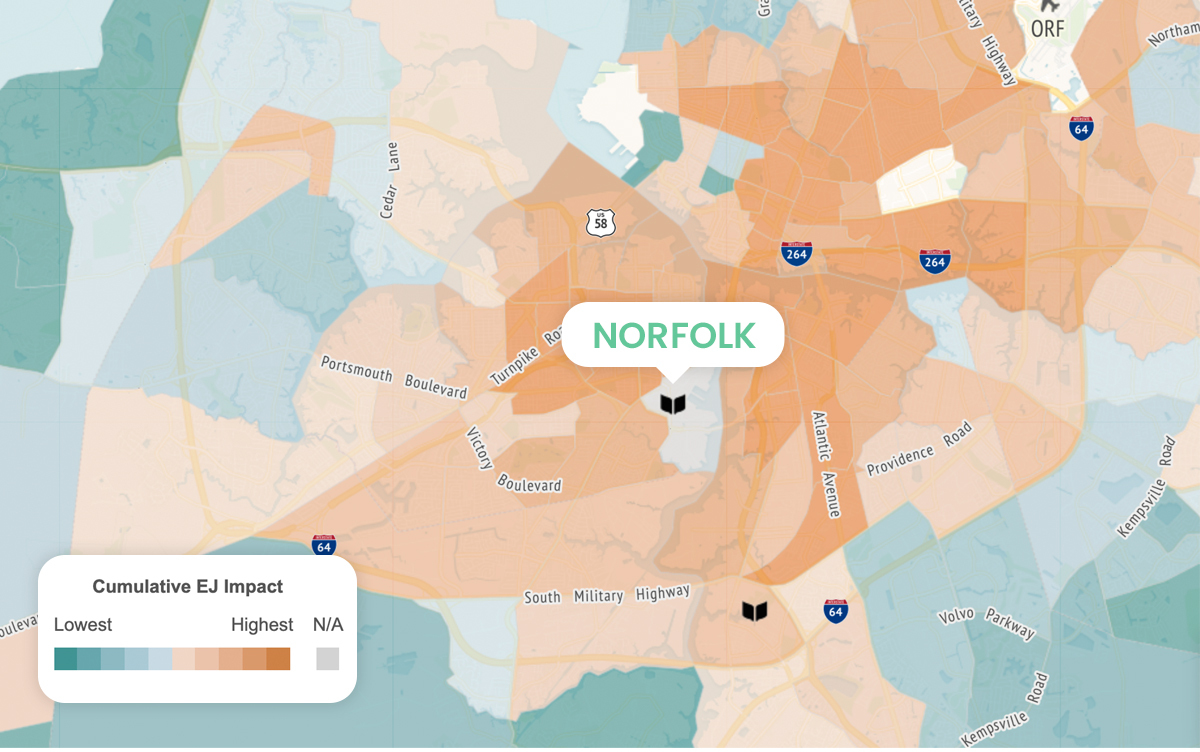

Cumulative Impact Map for Virginia drawn from Mapping for Environmental Justice, UC Berkeley, 2021, https://mappingforej.berkeley.edu/virginia/

In the late 1500s, Powhatan Peoples, with their rich wisdom and knowledge on local lands and waterways, tried to warn the colonizing invaders not to fill in the creeks and rivers with dirt but were ignored. The invader’s ignorance that hurt the Powhatan people and their lands is causing Norfolk and Naval Station Norfolk, the world’s largest naval base, to sink. Colonial violence and ideology were also the foundation for stealing thriving African peoples from their motherland as part of extractive thoughts and practices. Some African peoples were brought into Virginia and then enslaved for profit and free labor. In a geographical area where colonialism, white supremacy, racism, redlining, and environmental, economic, and racial inequalities have often destroyed and violated the lands, peoples, and waters, Hampton Roads remains to be a collection of communities and people worthy of not just being protected but of being healthy and thriving with sustainable futures.

Like Powhatan Peoples, Black people living in the Hampton Roads region for generations continue to be beautiful and present and deserving of living in communities protected from the water. Malik Jordan, a youth artivist (artist + activist) from the Young Terrace area in the St. Paul’s District in Norfolk, powerfully explains that the people should not be left to “be washed away” by the waters as climate gentrification is masked as the newest cycle of redevelopment. Primarily Black communities such as St. Paul’s, which lack protective sea walls, and where it floods even when the sun is shining, and where people are being pushed from the public housing are part of why Hip Hop Caucus began the Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project.

I’m energized by listening to people’s stories and trying to figure out shared solutions. That’s the work of an organizer.

This section explores the goals of the Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project (HROP). Additionally, it explores the creative and organizing processes that run parallel and intersect with each other during the first three phases of the project and how achieving goals, and the processes, have contributed to building community, shifting cultures, and expanding community power. Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) began envisioning the HROP in the summer of 2019, and it is currently a three-year project. The creative and cultural organizing project includes using comedy and films as cultural tools. As Rev. Lennox Yearwood Jr., HHC’s President and Chief Executive Officer, explains, comedy helps “to tell difficult stories, but also demand change”

HHC is a cultural advocacy organization that is grounded in hip hop culture. Using creativity and the arts is central to effective organizing because artists and creatives offer artistic representations of what they hear, feel, and know. Artists and creatives can also engage people differently than using dry facts and scientific data. Drew Veaux, a cameraperson and editor on the HHC post-production team for Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave (an HHC film), offers that using creativity makes movements less “sterile” and thus opens connections of possibilities between people and movements for social justice. According to Elijah Karriem, the director of Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave, there is an overall need for creativity in the approaches used for engaging people around the climate crisis. Karriem keeps it simple, “The last thing you want to be is boring.” Using the art of comedy as a cultural tool for engagement, the HROP began with the goal of mobilizing Millennial and Gen Z Black voters in the Hampton Roads region. The plan was to use comedy to help get out the vote in the 2019 statewide elections in Virginia, with voters being informed by the need for climate justice, equitable solutions for the climate crisis, and the protection of Black communities from flooding.

Through convening spaces, conversations, and events throughout the Hampton Roads region, the project is helping to build movement, shift cultures, and expand community power through sustainably engaging, mobilizing, and further connecting and amplifying various stakeholders from different subcultures. The project can be further understood by exploring the overall goals, the first three phases of the project, the goals within the phases, and the dynamic creative and organizing processes.

Week of July 15th, 2019

Climate Story Lab Convening

HHC Think 100%’s podcast, The Coolest Show, was one of 12 projects selected for the inaugural Climate Story Labs, which took place in NYC. Exposure Labs and Doc Society hosted the inaugural Climate Story Lab, bringing together 12 storytelling teams and 150+ issue experts to reimagine how storytelling can be used to accelerate climate action in the U.S. Over five days at New York City’s Auburn Seminary, media projects tapped into the collective wisdom of the funders, activists, and scientists in the room. Together, participants explored ways to reach new audiences and center the movement on justice and emerging youth leaders. At this convening, Center For Media and Social Impact (CMSI) ThinkTank was present and brought in five comedians to create concepts on climate comedy content (shows, skits, etc.). CMSI asked Liz Havstad to work directly with them based on the commentary she shared with the group. Havstad got to know them, and at the end of the week, they all said they would follow up and perhaps find ways to work together.

July and August 2019

Meetings With Climate and Clean Energy Equity Fund

Rev. Lennox Yearwood Jr. and Liz Havstad met with the Climate and Clean Energy Equity Fund (CCEEF). They discussed what climate justice and electoral strategies could look like for the upcoming 2019 statewide election in Virginia, focusing on Black communities and voters. CCEEF questioned what Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) would do if they had no constraints. The discussion evolved into doing a variety type show during Historically Black Colleges and Universities’ Homecoming season in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia to get out the vote and engage young Black voters on climate justice issues. HHC could film the show and release it and use the content for further mobilizing in 2020. CCEEF was interested in the vision, invited a proposal, and ultimately funded what became Phase One of the Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project.

July and August 2019

Meetings with Center For Media and Social Impact (CMSI)

Liz Havstad met with Caty Borum Chattoo in Los Angeles after the Climate Story Labs and let her know Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) may be moving forward on a variety type show in Virginia. Havstad also let Chattoo know HHC would like to bring in comedians for stand-up, sketch writing, and performances. While the proposal was developed with Climate and Clean Energy Equity Fund (CCEEF), Havstad worked out the budget process and the timeline for bringing on comedians to create the show. The timeline was very aggressive, but there was excitement to make it happen. Once the funding commitment came from CCEEF, HHC was ready to move forward with the project.

August 1, 2019

Recruiting Creatives

Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) spent three weeks recruiting comedians who would write and perform the show. They recruited a combination of stand-up comedians, sketch comedy writers, and stage and improvisation comedians. Since it was a variety show, the idea was to bring together a mix of comedy skill sets. Further, comedians needed to be available for the think tank, the writing weeks, and the actual live show. The writers and comedians confirmed were Bethany Hall, Tessa Hersh, Aminah Imani, Shantira Jackson, Clark Jones, and Yedoye Travis. While HHC was recruiting comedians, they were also looking for a director for the film part of the project, and eventually, Elijah Karriem was slated as the cinematographer. HHC engaged in various outreach and, via Antonique Smith, identified Matty Rich, who would come in as an Executive Producer and help with guiding a director.

August 13-14, 2019

Initial On The Ground Conversations In Norfolk, Virginia

Initial conversations were beginning with Hip Hop Caucus’ (HHC) Virginia Leadership Committee Coordinator, Charles “Batman” Brown II, and the Community Outreach Manager, Terence “TC” Muhammad. Discussions centered on the overall concept and ideas for the event, as well as venue options.

August 22, 2019

Venue Search

This trip to Norfolk was to do a walkthrough with Charles “Batman” Brown II at one of the potential venues called the Grandby, which is in downtown Norfolk. Terence “TC” Muhammad was also able to meet Norfolk State Administration, who informed him that Hip Hop Caucus’ initial dates would conflict with their already existing Homecoming schedule on campus.

August 27 - September 1, 2019

Comedy Think Tank Week

Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) held a six-day think tank at the office in Los Angeles with the comedians who had been recruited to participate. It followed a model that the Center For Media and Social Impact (CMSI) had used before, where the first day is all briefing of the comedians on the issues. HHC did presentations, and participants discussed the issue of climate justice. Then, for the rest of the five days, the writers and comedians came up with ideas and concepts for mostly sketches and how the variety show could go. Midway through, they presented initial thoughts, and on the last day, they presented everything to the HHC team.

Dejuan Cross, the HHC Music Supervisor, sat in on the first day because he would be working on music. Elijah Karriem was there filming the first day as well since his crew would be filming the show. Matty Rich, who later became a consulting producer on the project, was also there the first day.

A vital element of the creative trajectory kicked off this week via Yearwood when the comedians presented the concepts by the end of the week. Yearwood spent time emphasizing the question of where is the story of Norfolk in this and ended up pitching that the comedians be taken to Norfolk to film parts of the story there.

The organizing timeline was underway and continuing as Yearwood and Terence “TC” Muhammad internalized the critical situation in St. Paul’s while they were being shown around by Doug Beaver. Beaver explained to them the redevelopment plan for St. Paul’s from the perspective of the Office of Resilience in the Mayor’s Office. Ultimately this organizing work became the creative project, as the story of the community was a more extensive look into what was happening than the variety show.

August - November, 2019

Production Planning

In late September and October 2019, Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) scrapped the variety show script and transitioned to a straight stand-up show. There were already three stand-up sets within the variety show, so the HHC team asked the stand-up comedians to extend their stand-up sets, and the whole show would be stand-up, with an introduction from Yearwood and Antonique Smith.

Matty Rich took a step back at this point over creative differences. Rich had, however, already found Drew Veaux, who could edit the project, which was a critical find. There were also scheduling issues with some comedians because of moving the date and having other things going on with their schedules. Luckily, Clark Jones and Aminah Imani were able to accommodate the change. The HHC team also decided to bring on a local stand-up comedian to the show, and Charles “Batman” Brown II pointed them to Kristen Sivills as a popular local stand-up comedian. HHC also needed a host, and one had been recruited, but they could not attend, so HHC asked Mamoudou N’Diaye, and he jumped in the day before to host. N’Diaye had done some work with the climate movement with some previous projects, so he had some relevant material already.

September 2 - 13, 2019

Script Writing

Following the think tank week, the comedians returned home and were to write the entire show. The Center For Media and Social Impact (CMSI) Media was resistant to having the Hip Hop Caucus team review in-progress work so that the comedians could freely develop their ideas. Additionally, there was a handoff in leadership, as Bethany Hall kicked things off as co-head writer, and then she went onto maternity leave (which was planned), and Tessa Hersh took over from there as head writer for the group.

There were delays during this time for several reasons. The HHC team got the script three weeks before they were to stage and film the show at the Attucks Theater. There was also creative pushback on the script from members of the HHC team. The HHC team thought the script was workable and that the comedy could be effective, but that the content needed a deeper analysis of the climate crisis. The HHC team gave notes on reframing the content to be centered in systems change, racial justice, and climate justice, and the CMSI team realized they should have been sharing drafts earlier on in the process. CSMI was ready to do rewrites, but because of the time it would take to film all the scenes written for the show, it was not feasible to make the initial creative vision of a variety show happen. A decision was made by those involved to shift to a comedy show.

September 26-27, 2019

Meeting With Hampton Roads Influencers

Yearwood and Charles “Batman” Brown II met with influencer stakeholders such as local cultural influencers, promoters, urban, hip hop, and entertainment influencers. Lance Jones Jr., who works with Gaylene Kanoyton at the Hampton NAACP, participated in his first meeting to check things out. Kanoyton later attended a meeting where the Hip Hop Caucus team firmly understood that the community wanted to have conversations on the climate crisis and that mainstream environmental organizations are wrong that people of color do not care about this issue. Additionally, concerns over flooding are a daily concern. The Influencer Stakeholders wanted the Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project to address the climate crisis. The climate crisis was already front and center in terms of their concerns and thinking, and they saw no barriers to helping organize community members.

End of September/ Early October 2019

Event Date Moved and Continued Engagement

The comedy show at the Attucks Theater was planned to happen over two nights during the week of October 28th. However, Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) felt more time was needed to put a quality show together given where things were creatively. HHC pushed the dates to November and decided to use the week that would have been for the show to film documentary content that would be integrated into the show. HHC would be doing GOTV outreach while also building the audience and organizing for the event in November so that the event would be a continuation of engagement around the election. The strategy was to turn out voters on climate justice and then bring folks together on the issues via the event at the theater as a culturally relevant advocacy organizing tool.

October 1-4, 2019

Meetings With City Officials, Radio, and Community Organizers

Terence “TC” Muhammad met with Toiya Sosa, who was excited and loved the project. Toiya had worked with Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) on Respect My Vote! campaigns in 2012 through Virginia National Urban League Young Professionals and shared a list of local VIPs. Charles “Batman” Brown II and Muhammad attended a meeting at 103 Jamz (a hip hop station on iHeart Radio). There were discussions on running ads to help promote Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave and get the message out to the public. Additionally, Muhammad met with the local leadership of the Local Mosque (NOI) to discuss outreach to the community, for which they offered support and requested marketing materials. During this trip, Muhammad also went to the Attucks Theater for the first time.

On October 3rd, 2019, there was a meeting attended by Gaylene Kanoyton, Yearwood., Lance Jones Jr., Brown, and Muhammad. Kanoyton was a key local stakeholder in connection with the organizing processes. Kanoyton is connected throughout the seven cities in the Hampton Roads region and is the President of the Hampton NAACP Chapter and associated with an organization called “LINKS.” She also has a history of working with HHC on the VA State Table in 2012, when HHC ran that table.

Critical parts of this discussion focused on big environmental organizations who pitch climate through talking about polar bears, plastic straws, recycling, and the like, who do not come to the community to talk about saving lives. These types of talking points do not connect/click with local stakeholders and do not sound authentic. There was an appreciation that HHC presents climate justice issues in a way that the issues can be taken by someone like Kanoyton to clergy, to community leaders, and to her entire network of community and political leaders. Kanoyton and Jones expressed appreciation for HHC’s work with communities after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

October 6-11, 2019

Meetings With Religious and Community Leaders, and Other Logistics

Yearwood and Terence “TC” Muhammad met with Pastor Dwight Riddick of Gethsemane Baptist Church – a megachurch in Newport News with 5000 – 10000 members. The Pastor let the Hip Hop Caucus team know that the climate movement has never approached the clergy. The Pastor also talked about flooding and wanting his church involved in whatever they could contribute. The church already has its evacuation plans, and they wanted to look at the old pipes in the houses in their old neighborhoods. Conversations began with the Attucks Theater staff around this time. Muhammad checked on hotel options for the HHC team members, comedians, and film crew. He also met with Angela Harris with the Southeast Care Coalition in Newport News, who was involved with HHC’s Act On Climate Tours in 2014 and 2015.

October 14-18, 2019

Meetings With Religious Leaders, Mayor Kenneth C. Alexander, and Other City Officials

Yearwood and Terence “TC” Muhammad attended a breakfast that Gaylene Kanoyton brings together a couple of times a year at Gethsemene Church. A lot of pastors of big churches and leaders of organizations attend these events every year. They had lots of questions on flood evacuation and what to say on the issue of climate change. Everyone was very engaged and wanted to know the next steps. They thought it would be good to have a page of resources around evacuation plans, and they wanted to know how they could more effectively talk to their parishioners. They also want to create an environmental theology and maybe create climate and environmental groups in their church.

Yearwood, Muhammad, and Kanoyton also met with the Mayor of Norfolk, Kenneth C. Alexander, and Adisa Muse, Chief Deputy City Clerk. The Mayor wanted the HHC team to know how much they are doing around climate and resilience and that the city is in full support of HHC bringing our event to the city. He shared what is going in Hampton Roads, Suffolk, Old Dominion University (ODU), and Norfolk State University (NSU) and discussed a resilience program they are instituting and adapting. He shared that the city was 100% invested in The Attucks Theater’s 100th Anniversary and was also very clear that the city is sinking below sea level.

The HHC team met with Andria McClellan, one of the city council members working on climate. She is the council member who is most connected to the large environmental organizations and is the green government person who talks about the climate. She is the white member of a Black city council and wasn’t used to people of color leading the conversation on the climate.

In a later meeting, Angel Brown, with iHeartRadio, offered to promote more on their radio stations than was initially offered. They had not done anything before on climate in the market, and Kanoyton suggested doing a climate minute. The HHC team also met with Rob Cross, who runs the art scene and runs VA Arts Festival. The team discovered that Old Dominion University has 4D cameras and a studio, and so does Norfolk State University, where folks in the arts community can come in. Cross let the team know they are a non-profit organization, and they get most of their funding from the City of Norfolk. He was familiar with the Attucks Theater in and out from filming there and offered insights. The Attucks Theater is older than the Apollo and was founded, created, and financed by people of color. Muhammad also had a chance to visit the Attucks Theater.

Yearwood and Muhammad met with Doug Beaver and Kyle Spencer from Norfolk’s Office of Resilience. The HHC team learned the role of their office around climate change and the rising sea levels. Beaver and Spencer allowed the HHC team to see maps of the city and the plan to deal with rising sea levels in the downtown and other Black and Brown communities.

October 27-31, 2019

NAACP Meetings and Start Of Filming

The Hip Hop Caucus team started getting a lot of film footage of influencers and community members, and comedians. There was also a shootout that happened right around the Teens With a Purpose center. Clark Jones, one of the comedians, was outside going to the store when all of this happened. Jones had to dive under a car. The police came, and he was really affected by the shooting.

The film crew also filmed at the Naval base with Deirdre “MomaD” Love, Yearwood, and some of the comedians. Yearwood and Muhammad attended a meeting with the NAACP Centering Equity in the Sustainable Building Sector to continue building outreach for the actual show.

There was a meeting with Felicia Davis with the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Green Fund. The HHC team was trying to engage the larger VA NAACP coordinators around climate change issues and inform them of Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave. Gaylene Kanoyton also set up a political meet and greet in Virginia Beach, where Yearwood was the keynote speaker. The camera crew was on hand to record it. Yearwood was also on a Christian radio station and continued his outreach efforts by attending a United Negro College Fund event.

Week of October 28th, 2019

Documentary Story Shoot

Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) used the week that would have included the original event dates to bring the comedians that were still on board for the stand-up to Norfolk to shoot some documentary elements that would be woven into the show. HHC brought on local comedian Kristen Sivills for the show so she could participate as well. The footage that resulted was worked into the live stage show at Attucks Theater, was worked into Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave, and is the foundation for Underwater Projects.

The opportunity to be embedded in the community deeply informed the comedians who would be performing the stand-up on what was happening locally before their performances at the Attucks Theater the following month. The community members interviewed during this week reflect the organizing work. The comedians’ involvement was also part of the organizing tactics for the live show, building deeper connections to the climate issues among stakeholder groups in the region and the long-term vision of the work.

November 6-11, 2019

Street Promotions And Teens With A Purpose Gala

Ricky Beldo and his street team came up from Atlanta to start going throughout the city to pass out flyers and put up posters. The Hip Hop Caucus team had them start in the five communities closest to the Attucks Theater and where the center for Teens With a Purpose (TWP) is housed. Charles “Batman” Brown II and Terence “TC” Muhammad helped coordinate where the best places to put up and pass out marketing materials were. TWP had its Annual Gala, and Yearwood brought words to the crowd. He also did a radio show at Old Dominion University to continue promoting the Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave comedy shows.

November 13-22

Ain't Your Mama's Heat Wave Live Shows and A Leadership Roundtable

This week, the show occurred, and everyone from Hip Hop Caucus (HHC), comedians, videographers, and more came into town. Everyone completed walkthroughs, rehearsals, and filming with comedians and other community members. The comedy shows were filmed on November 20th and 21st, with the first night being for VIP stakeholders. The HHC team was regularly attending meetings with each other and participated at The VA Leadership Roundtable meeting at the Slover Library as part of a larger conversation around culture and climate justice led by leaders of the Climate and Clean Energy Equity Fund and the HHC team.

November 20 - 21, 2019

The Events At The Attucks Theater

The comedy shows took place over two consecutive nights, November 20th and 21st. November 20th was an invite-only VIP event that included local stakeholders from various subculture groups. November 21st was open to the public. The decision to have the performances laid out this way was part of the organizing strategy that included bringing together various stakeholders from different subculture groups to build movement, shift culture, expand community power.

(MEANT to be January 2020 through April 2020 but has really been January 2020 to the present day, but the scope of the research project ends in December 2020)

January 16 - 20, 2020

First Trailer Cut

The Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) post-production team spent a week editing the first trailer for the project, which was still one film at this time. This trailer was the first look at the story the creative team was telling. HHC privately shared the trailer with their networks and stakeholders, and there was an overwhelmingly positive response. The HHC team knew that they had something great but needed to take a break to recuperate and take a step back for reflection before post-production continued.

January 22, 2020

dream hampton Added As Executive Producer

Liz Havstad reached out to dream hampton to see if she would be interested in coming onboard the project. A creative lead was needed, ideally a director, since a director was not brought on initially despite trying because of the short timeline and changes within the creative team. Hip Hop Caucus brought on hampton as an Executive Producer with a creative background.

January 23, 2020

Follow-Up Meeting of Influencers

Yearwood hosted a sneak peek of the Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave film for influencers at the Slover Library in Norfolk.

February 3 - 21, 2020; March 10 - 13, 2020

Post-Production Editing

The first round of editing of the film as a single film began.

April - June, 2020

Figuring Out What Was Next

COVID-19 hit, and sheltering in place started in Los Angeles the week after the Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) post-production team finished the first edit on the film. The team had planned to continue post-production in April and May with a Sundance Film Festival submission deadline as the target date. However, everyone was adjusting to what the impacts of COVID-19 would be. Additionally, further uprisings around the killing of George Floyd were part of HHC’s work, and the world was changing around the need for racial justice.

By June, the HHC team had devised a plan to split the film into two different films–the comedy special, Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave, and the documentary, Underwater Projects. The HHC team knew they wanted to finish Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave as soon as possible and were shooting to get Underwater Projects completed enough to submit to the Sundance Film Festival.

July - September, 2020

Post-Production Animation

The Shapes + Forms motion graphics offices are in the same place as Hip Hop Caucus (HHC) offices in Los Angeles, so HHC had known they produced quality content for a few years. Although the HHC team did additional outreach for motion graphics companies, the team showed Shapes + Forms work to dream hampton. They participated in an introductory conversation, and it felt like a good match. Because it was literally at the time of the George Floyd uprisings, Shapes + Forms was genuinely interested in helping make the motion graphics interstitials happen because they wanted to do something for the movement and completed the whole project at cost for HHC. Their regular clients are more corporate than HHC, so they took this on as an opportunity for passion and contribution to the movement.

The HHC team identified the writers of the interstitial scripts via Center For Media and Social Impact (CMSI). Mamoudou N’Diaye was already a part of the stage show, and Joseph Clift was someone CMSI had worked with on one of their previous projects. The HHC team knew they wanted Black and Native writers (specifically because of a Native American-focused interstitial). Bethany Hall led the writing process with N’Diaye and Clift, Havstad did the research to ground the writing, and hampton and Havstad reviewed and edited for the Underwater Projects the storylines.

July 6 - July 29; August 14, Sept 2; 2020

Ain't Your Mama's Heat Wave Post-Production

Edited Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave as a comedy special film for four weeks. Editing was picked back up to finalize the film in 2021 in time for the DC Environmental Film Festival.

July 29 - October 2, 2020

Underwater Projects Post-Production

Over nine weeks, the Hip Hop Caucus team edited and finalized Underwater Projects as a documentary to the point of being able to submit the film to the Sundance Film Festival on October 2nd, 2019.

December 31, 2020

Ain't Your Mama's Heat Wave Submission to DCEFF

A nearly completed version of Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave was submitted to the DC Environmental Film Festival in December 2020 and was accepted to the festival in 2021. The Hip Hop Cacus post-production team finalized the film in the form of sound mixing, coloring, and credits in 2021.

(April 2020 and beyond, but the scope of the research project ends in December 2020)

The Pandemic continued and impacted 2020 organizing and engagement plans as the world lives in a changed reality. Additionally, uprisings were shifting conversation on the need for racial justice.

April 20, 2020

50th Anniversary of Earth Day

A 15-minute clip of Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave was shown that included Yearwood speaking on the importance of utilizing culture and comedy to tell a story on the need for climate justice.

July 24, 2020

Ain't Your Mama's Heat Wave Sundance Trailer Shown In NYC

Mamoudou N’Diaye, the host for the live comedy shows at the Attucks Theater, shared the Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave trailer with Climate Town during the Sundance Film Festival. Climate Town presented An Inconvenient Livestream: Climate Justice, a show in New York City that talked about racial injustice and the climate crisis.

Hip Hop Caucus developed the overall goals of the HROP over the summer of 2019. The goals were initially designed to engage and empower Black Millennial and Gen Z cohort members as part of Homecoming events at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the lead-up to the 2019 statewide election in Virginia. A creative component of this project was to be cultural events in the format of a variety show (including sketches, comedy skits, and more) called Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave that would address the climate crisis through humor in culturally responsive ways. There ended up being two nights of stand-up comedy at the Attucks Theater, a historical Black theater located in the St. Paul’s community, funded and built by Black entrepreneurs in 1919 for the Black community that still serves Black communities. The events allowed diverse stakeholders to practice joy as part of resistance, as has historically been practiced by Black communities pursuing human and civil rights.

Although the HROP goals were developed to connect with HBCUs’ schedules, the very nature of creative and organizing processes demands responsiveness and fluidity. Even with a tragic global pandemic and necessary uprisings for racial justice, the overall goals were still primarily achieved—just in different ways that could not have been anticipated. The original project goals were to:

Understanding the creative and organizing processes that were in motion and that helped achieve these goals can be more deeply understood by individually examining the first three phases of the project.

Flowers, Corei. “Homecoming and HBCUs: Defining Our Culture: Her Campus.” Her Campus, 29 Sept. 2020, https://www.hercampus.com/school/hampton-u/homecoming-and-hbcus-defining-our-culture/.

Phase One began in the summer of 2019 and ran through December of the same year. The project started with research, building relationships with stakeholders in the Hampton Roads area, and creative visioning. In this phase, the creative and organizing processes informed each other as information was gathered and ongoing events impacted their trajectories. Havstad explains that the Think 100% Hampton Roads Organizing Project (HROP) approach is about:

“Building political power through elections and advocacy with climate justice and the particular alignment of Black communities and Black voters in the Hampton Roads region with the issue of climate justice to move the needle further and farther on climate action and a just transition.”

Part of the vision for this project was crafted through discussions with the Climate and Clean Energy Equity Fund, which eventually provided funding that helped to support the developing organizing and creative processes in Phase One. Additionally, a collaborative relationship important for the HROP is with the Center for Media and Social Impact (CMSI), based at the American University’s School of Communication. The seeds for this relationship were planted at the inaugural Doc Society Climate Story Labs event in New York City in 2019.

Within the organizing processes, core members of the HHC team were on the ground throughout Hampton Roads such as Havstad, Muhammad, Yearwood, and Charles “Batman” Brown II (the HHC Virginia Leadership Coordinator at the time). They were driven by the fact that the tragedy and loss of lives, particularly Black lives, in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina can happen in Norfolk. The team traveled through communities, listening to and learning from diverse stakeholders about community needs and experiences connected with climate justice while searching for a venue. As with other communities across the globe where there is injustice, people are already fighting for justice, even if not climate justice specifically. Because HHC works to include everyone willing to join together to fight for climate justice, not just those who may directly sign off on policy changes, they seek out stakeholders from across subcultures. The HHC team met with a broad collection of stakeholders, including politicians, civil rights leaders, entertainment influencers, community leaders, activists, and more, about how flooding, gentrification, and the climate crisis were being addressed in the communities and by other organizations in the climate movement.

The HHC team learned that if organizations within the climate movement were engaging stakeholders (which they often had not), they were more apt to speak about polar bears and recycling than about the vulnerable lives at risk in the primarily Black communities in the region that are already flooding and lack protective sea walls. Stakeholders such as Pastor Dwight Riddick of Gethsemane Baptist Church, Lance Jones Jr., and Gaylene Kanoyton from the Hampton NAACP spoke with the HHC team about the need for safe evacuation routes and the impacts of the flooding. They were creating some of their own solutions by educating the community and parish members. However, they made it clear that they were not being engaged around climate justice but wanted to be and wanted to learn how, in their respective roles, to speak more knowledgeably with others about the issues.

Deirdre “MomaD” Love, the Founder and Director of Teens With a Purpose (TWP), a community empowerment program for teens in the St. Paul’s District, is another influential community stakeholder with whom Yearwood and Muhammad began to build a relationship. Love and youth participants of TWP, inspired by Jordan as a younger participant, started a community garden years earlier and were already creating solutions to help counter the impacts of pollution and food scarcity in St. Paul’s. Love also has a comprehensive knowledge of the history and cultures in the area. The importance of genuinely building sustainable relationships with community stakeholders that are not simply forged to serve the wants and needs of organizations is a theme that came from interview participants. People in a community may not understand climate change, but they know their life experiences. They may be living through numerous forms of trauma and need to focus on the most immediate issues they are facing. Meeting people where they are is fundamental to creative and cultural organizing. Being responsive to communities that other organizations had not been engaging with around the severity of the threats they faced indicates HHC was committed to being as responsive and sensitive to the community as they had been within other organizing projects and campaigns.

From August through November 2019, members of the HHC team attended meetings and community events and helped host and convene spaces. These meetings and events can be explored in great detail on the interactive timeline in this presentation. Through talking with, listening to, and connecting stakeholders who may never have been in conversation with each other or included in discussions around climate justice, along with education, HHC was helping to build movement and expand community power through sustained organizing and community engagement. Within the organizing processes, stakeholders began increasing their ownership of the local climate conversations. Increasing ownership of the narratives and needs of their communities for climate justice is part of shifting the culture of engagement within the climate movement. The organizing processes that began in this phase were part of laying the critical groundwork for understanding the needs and wants of the community and being able to organize. Including stakeholders in the organizing work towards solutions from the beginning, not as an afterthought or in passive roles, helped lay the foundation for sustained engagement. The organizing processes were not isolated from the creative processes—the processes began a symbiotic relationship that continues to this day.

The creative processes in Phase One were firmly centered on the creative vision for the live creative and cultural entertainment event, identification and education of writers and comedians, and navigation of promoting and putting on a successful show that people could enjoy and that would help to mobilize voters. However, the creative processes were grounded in HHC research and previous creative and cultural organizing work by HHC in Virginia through campaigns such as Respect My Vote! As part of creative processes, the HHC team members on the ground in Hampton Roads at different times were, including, but not limited to, Havstad, Muhammad, Yearwood, and Brown. While locating a venue, they built crucial relationships that helped create avenues for promoting the show through radio stations, a local mosque, cultural and entertainment influencers, and universities and colleges. All of these pieces were necessary to build and have an impactful event. While organizing processes were in motion, the vision for the comedy show was developing within the creative processes.

In collaboration with CMSI, the HHC team identified writers and comedians and provided them with a grounding in the climate crisis, the need for climate justice, and the community of Norfolk. Over three weeks, the HHC and CMSI teams recruited a combination of stand-up comedians, sketch comedy writers, and stage and improvisation comedians who could be available for a think tank and the writing time needed to complete the show. The comedians selected also need to be available for live performances in Norfolk. The writers and comedians confirmed were Bethany Hall, Tessa Hersh, Aminah Imani, Shantira Jackson, Clark Jones, and Yedoye Travis.

Once the teams identified the writers and creatives, there was a six-day think tank in Los Angeles. On the first day, the HHC team used a model developed by CMSI, where the writers and comedians were briefed on and immersed in frameworks for thinking about climate justice and racial justice. Also present on that first day were Havstad, Karriem, Dejuan Cross (HHC’s Music Supervisor), Matty Rich, and Yearwood. The comedians and writers spent the remainder of the five days ideating jokes, sketches, and ideas for a variety show. The HHC team, including Yearwood, is committed to ensuring that all artists and creatives they work with understand the issues and can internalize how serious the threats are from the climate crisis, particularly for Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities. Even with providing education, when the writers and comedians presented their content at the end of the think tank, Yearwood pushed for more inclusion about the situation in Norfolk.

The HHC team decided to take the comedians to Norfolk in October of 2019 to begin internalizing what is happening to help inform how they would complete the writing for the live shows. Due to script delays and other factors, the original variety show concept changed to a comedy show concept in September, so the comedians were learning for their own knowledge and material. In August and beyond, Yearwood, Muhammad, and Havstad had been able to meet with Doug Beaver and Kyle Spencer from the Office of Resilience several times and had gained vital information about the redevelopment plans for St. Paul’s. The community understood those plans as gentrification and the “debeautifying [of] the hood.” The plans came to be understood by the HHC team as part of a pressing climate gentrification story that needs to be told. In this way, organizing processes were informing creative processes, including the immersion experience of the comedians.

The comedians needed to understand the local history, culture, flooding, climate issues, dynamics, and stakeholders. Havstad offers:

“We had come to a really clear understanding that there was this climate gentrification story in front of us where the public housing community was being planned to be relocated. And all the dynamics between the Mayor’s Office, the city council, the community developers, climate scientists, and the Navy were intersecting on this one project, and everyone had their agendas and those challenges.”

Yearwood emphasizes:

“We believe in an Ella Baker mentality of organizing. Meaning, that this isn’t focused just on the comics and everything around them, but on the community and on a community struggle. The Ella Baker mentality is that we all do this together, or we don’t do this at all.”

The film crew, all people of color, were also present and documented the comedians speaking with various stakeholders while also filming documentary footage in the community. Comedians and the community had opportunities to begin to build solidarity. Culture began to shift with the comedians as they began informing their art with what is happening on the ground, the people and local cultures, and connections between flooding and the climate crisis in Norfolk. Making the comedy shows more community-based included bringing along a local comedian, Kristen Sivills, from Virginia Beach, VA. Sivills shares:

“I was almost scared to be the one person that was from the actual area in the comedy show. But going around to the different places that we went to before, just kind of digging into the history of what has been going on in the area, I learned things that I didn’t know. But it was also interesting to see how other people reacted to just the history here in Virginia Beach.”

The opportunity for the HHC team members, comedians, and people in Norfolk to learn as creatives or other stakeholders within the creative and organizing processes is a holistic approach to building movement and expanding community power. The opportunities include pathways for shifting cultures in many ways, from learning about what is happening in one’s community, such as that the flooding is not just “normal,” to impacting how stakeholders engage with each other, such as Brown and Love building a lasting and supportive relationship, to shifting the narratives within communities about the need for climate justice as racial justice and from where the solutions can grow.

Phase One provided a fertile foundation for organizing and creative processes to move forward. The processes were in synch with each other, informing each other. This synchronicity resulted in two successful comedy shows about the climate crisis at The Attucks Theater in November 2019. While the HHC team was planning the show, GOTV outreach was also being done while building the possible audience and organizing the event to continue engagement around the election. The strategy was to bring together different stakeholder groups to build movement and expand community power through collective cultural and advocacy experiences to help drive people to the polls with a climate justice lens. Over two nights, the first for VIP stakeholders such as entertainment and culture influencers, and the second night for the equally essential community stakeholders, including the Mayor of Norfolk, Kenneth Cooper Alexander, hundreds of people came together to practice joy.

The comedians present for the shows, all of them Black, were Clark Jones, Aminah Imani, Kristen Sivills, and Mamoudou N’Diaye. Antonique Smith, an artivist who has worked with HHC on climate justice for several years, and Yearwood hosted the shows. The shows also included Malik Jordan and Tiffany Sawyer, who are artivists, youth poets, and organizers with Teens With a Purpose. They presented a poem on including youth voices in the discussions on the “debeautifying” happening in their communities. The film team successfully documented the shows on both nights. Their work resulted in large amounts of footage for creating films to uplift what is happening in Norfolk and provide a joyful night for others in communities across the nation being impacted by the intersecting injustices Black people live with every day.

HHC established the HROP and phase goals to engage and connect a diverse body of stakeholders across various subcultures, disseminate information, mobilize people to the polls, document the positions and experiences of the people and communities throughout Hampton Roads, and put on live creative and cultural events. These goals were all successfully achieved. Yet, achieving these goals is better understood as successful because building movement and expanding community power were made possible through convenings, education, voting, and opening doors for sustainable engagement with and between stakeholders that continues in 2021. Additionally, the shifting of cultures occurred artistically, within and across stakeholders through ownership of climate narratives and solutions, and through creating culture. This provided opportunities for organizers, artists, creatives, stakeholders, and other community members to reimagine how arts and culture, particularly comedy, can be used for engaging and centering communities being impacted by the climate crisis and shift narratives on climate justice as racial justice.

Throughout Phase One, HHC and stakeholders in Norfolk and the broader Hampton Roads region built a foundation. The HHC team also began adding to and shaping the components of a proof of concept that using creative and cultural organizing strategies can help to spark imaginations for the infinite possibilities of providing joy while bending the arc of climate justice closer in communities most at risk and those already being impacted by the climate crisis. The fluid organizing and creative processes set in motion in Phase One did not stop at the temporal boundary of the phase. They were set in motion to flourish and build on. As the project moved into Phase Two, creative processes would be front and center but still interconnected with organizing processes.

Tidwell, Mike. “Will Norfolk Be the next New Orleans?” Pilotonline.com, The Virginian-Pilot, 7 Aug. 2019, www.pilotonline.com/opinion/columns/article_27fde306-329f-5d63-89d1-544196cbcd5c.html.

Fella, Alexander, director. Changing Tides: Gentrification in Norfolk. The Urban Renewal Center, 2019, https://theurcnorfolk.com/gentrification-in-norfolk-forum.

Phase Two began in January 2020. The main goal was to complete a film and release it through HHC’s Think 100% Platform, specifically the Think 100% Films division, using the footage from the comedy shows while including other documentary footage captured to provide community and stakeholder contexts and stories. Please note that emphasis on creative goals in this phase in no way indicates that organizing processes, including maintaining relationships and open lines of communication, ever stopped. Creative processes are as fluid as organizing processes. However, they sometimes have more firm deadlines, and the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the timeline of the entire world.

In mid-January 2020, the post-production team, including Veaux (the editor) and Havstad, completed a trailer for what was envisioned as one film. HHC privately shared the trailer and received a solid response; however, they felt some time was needed to reflect on the vision and recuperate after an intensive process. Shortly after, dream hampton, an award-winning director, was brought on as Executive Producer, bringing a vast pool of knowledge to the creative filmmaking process.

In February and March of 2020, the first round of editing began to create a single film called Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave. Yet, the world was changing as COVID-19 began to strike communities across the globe, and uprisings began around the killing of George Floyd by the police and the urgent need for racial justice. In the second half of March, the post-production team completed their first full edit of the film as sheltering in place began in Los Angeles. As Havstad, dream hampton, and Yearwood reflected and evaluated the stories within the film over two months, it became clear the film would need to be broken into two projects. One project would be Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave, a comedy special on the climate crisis. The other project would become Underwater Projects, a documentary on what is happening within the Hampton Roads region, particularly Norfolk, in relationship with the climate crisis, race, climate gentrification, and the risks that communities and Naval Station Norfolk, the largest employer in the region, face.

It turned out that Phase Two for creative processes would extend into what is identified as Phase Three, which began in April 2020 for organizing processes, resulting in the phases running concurrently. This is discussed more in the Phase Three section of this presentation; however, this eventual crossover illustrates how fluid creative and cultural organizing strategies and processes need to be. This moment is where creative processes expanded while also increasing opportunities for future organizing with two films as creative and cultural organizing tools. Given that films produced from organizing projects should further serve organizing goals, the creative processes needed to move temporally different at times; however, they remained parallel with and intersecting with the organizing processes.

There were distinct goals for each film that demanded different timelines and editing processes. Deciding to create two separate films opened pathways for more effectively serving the stories being told and using the films to organize in the future. Editing helps define the narratives of stories being told through film, and the editing process brought clarity on what was possible with the content on hand. Comedy specials and documentaries are two different genres of cinema — one being more linear to edit and one having the capacity to hold diverse story arcs that all feed into the stories that the people or organizations involved in producing them seek to share or amplify. Veaux shares:

When it was just all one film, when we were just trying to pack everything into this one film, the film felt way too long first and foremost… and when we tried to cut it as one film, there wasn’t enough climate crisis jokes to cut to. So, that was the problem there because we were cutting from documentary stuff and then to jokes that didn’t even involve the climate crisis, so that was a bit jarring.

Care must be shown with editing documentaries, and that involves being sensitive to the community. Creating two films not only allowed for distinctions between comedy and documentary films, but it also enabled this type of care to be present in an elevated way.

The HHC team continued forward with a plan for the two films beginning with a heavy focus on the documentary. The goal was to complete the basic editing of Underwater Projects for submission to the Sundance Film Festival. To meet an October 2020 deadline for the festival would include further defining the story arcs, editing, sound mixing, and motion graphics. To help meet this deadline goal, Mandolyn “Mystic” Ludlum (the author of this research project) was brought on as a project coordinator to work with Havstad, Veaux, Cross, dream hampton, a motion graphics team, and others. The process for interstitials needed to start as soon as possible.

Interstitials are short pieces shown between film elements, which in HHC’s context are motion graphics pieces that connect different story arcs and are essential for including context for viewers of Underwater Projects. The urgent climate stories that need telling through films mandates placing stories from places such as Hampton Roads within historical, conceptual, and cultural contexts. These contexts are meaningful because they allow viewers to understand better what is happening in Norfolk. Additionally, they are essential so that viewers in communities affected by the climate crisis can know that what they are experiencing is part of the expansive and ongoing structural violence and systemic exploitation, in addition to the inequalities, oppression, and destruction that has grown from colonial, white supremacist, and capitalist ideologies and practices.

Love emphasizes that people who are being harmed through environmental racism need to see the types of films HHC is making. Love says:

A person who doesn’t see a movie like that or see a documentary that tells the whole story would own a part of that, that isn’t their own…I feel strongly that we need to hear as often as possible all the things that contribute [to harming communities] so that we see ourselves as whole and that we’re really uber resilient to survive through things that should have killed us a long time ago.

HHC hired Shapes + Forms in July 2020 to create the motion graphics that would help provide the necessary contexts in an understandable and accessible way. Shapes + Forms is a company that primarily serves corporate companies, but they wanted to support the justice movements that were ongoing during this time. They provided their motion graphics work at cost (the cost of the work supplied without a profit margin), which allowed HHC to move forward within any financial constraints.

The Center For Media and Social Impact (CMSI) and HHC worked together on the scripts for the interstitials. Inclusion is a priority for HHC, and the team knew they wanted Black and Native writers due to the content being written and the history of Hampton Roads. Bethany Hall from CMSI managed the writing team, including Mamoudou N’Diaye, who hosted the live comedy shows in Norfolk, and Joseph Clift (a comedian and writer). Havstad helped to do the background research and drive the writers’ content, while dream hampton and Havstad reviewed and edited for Underwater Project’s storylines. Over the next few months, there was a constant exchange of feedback between the HHC post-production team, the CMSI team, and Shapes + Forms on motion graphics content, comedic timing, and effects, all while Underwater Projects was being edited overall. Having a hard deadline for the Sundance Film Festival was helpful as a guide for how time was navigated.

In a significant happening, HHC secured the famous comedian Wanda Sykes, a Hampton Roads native, to record the audio for the interstitials right before the Sundance Film Festival deadline. Both Clift and N’Diaye had previously recorded the audio, but getting someone from Hampton Roads, who is also well-known, was considered a win, and Clift and N’Diaye were supportive. Although the festival did not accept the film, HHC gained a deeper understanding of filmmaking and the additional footage needed to flesh out the storylines on the need for climate justice, the continued impacts of climate gentrification, and the sinking Naval Station Norfolk.

The goals for Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave in Phase Two as a distinct film were to complete the film and then secure distribution and continue organizing and mobilizing work in Virginia and other states during the time leading up to the 2020 elections as part of Phase Three. The HHC post-production team and CMSI team tightened up the film through editing and feedback loops. With an almost completed comedy special on hand, and a firm belief in the power of comedy to open conversations on something that is not funny at all, the climate crisis, HHC began submitting to film festivals and using and providing clips for organizing and to organizations in the climate movement. Beyond this project’s scope, the film was finished entirely (i.e., editing, color correction, sound mixing, credits, and music clearances). Moving from a goal of one film to having two films and engaging in creative processes on two fronts demanded fluidity, flexibility, and additional financial and human capacities. Additionally, it required a firm commitment to creating creative and cultural organizing tools that are birthed from the needs of a community while pursuing climate justice, building movement, shifting culture, and expanding community power. HHC stayed the course as part of long-term creative and organizing processes grounded in a commitment to serving communities.

The HHC team made decisions within Phase Two that expanded the nature of the creative goals and processes, and this meant the phase would continue to run parallel with Phase Three. Additionally, the arrival of COVID-19 as a global pandemic contributed to creative and organizing processes no longer moving from one finite phase to the next. However, the goals for Phase Two are considered to have been successfully met. Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave was completed enough as a film in Phase Two to become available for the film festival circuit and exploring distribution options. Although HHC could not use the film as envisioned for in-person organizing purposes leading up to the 2020 elections, that does not mean the film could not still be successfully used as a creative and cultural organizing tool.

As an organizing and advocacy phase, Phase Three began in April 2020, and like Phase Two, continues at the time of this research project being made available to the public. As previously explained, neither the organizing nor creative processes set in motion in Phase One cease to move when one collection of processes may take more of the prominent position. The first official use of Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave as part of organizing processes was in January 2020. At that time, Yearwood used clips of the film as part of a stakeholder follow-up meeting with local influencer stakeholders at the Slover Library in Norfolk. This event was before any film clips were shared outside of the project’s communities. This event represents sustained engagement with the community and stakeholders that HHC sought to engage at the beginning of the HROP. People in the community were excited about the comedy shows when they happened, and showing how the film was developing was another valuable moment for building movement.

When a film does not grow out of an organizing project or is not being used as a creative and cultural organizing tool, it may wrap and charge forward driven by corporate purposes such as box office numbers. HHC does not organize nor produce creative and cultural events that are extractive to the communities being engaged. They consider present and future organizing as part of the often necessary long-term commitments to communities and those needed to further climate justice and other areas of social justice.

As the world continued to navigate a changed reality due to COVID-19 and uprisings, HHC shifted to thinking about how to affect change, educate, and shift culture through virtual platforms. The plan for the HROP organizing processes was to use Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave clips and discussions as part of localized non-partisan organizing and mobilizing events to get out the vote for 2020 national elections with the same push for climate justice and racial justice used in Virginia in 2019. The plan included expanding outside of Virginia to include additional states through using creative, cultural, and geographically relevant approaches. In place of in-person events, HHC continued organizing through its long-running Respect My Vote! platform, a voter registration and mobilizing campaign, and as part of broader strategic plans. Additionally, they provided content for partner’s virtual events. This organizing work continued HHC’s overall work on the inclusion of climate justice as an issue in all of their campaigns to get out the vote.

Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave is a comedy and brings joy, but it is also an organizing tool, and anywhere that clips or the film are shared is considered to offer opportunities for organizing. Within the scope of this research, film clips were shared in April 2020 by Yearwood as part of celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Earth Day. Additionally, the trailer was shown in July 2020 as part of Climate Town during the Sundance Film Festival, and HHC submitted the film to the 2021 DC Environmental Film Festival (DCEFF). Outside this research project’s scope, DCEFF accepted the film into the festival as the first climate crisis stand-up comedy film in their history. It became the third most-watched film overall during the festival, and the film’s inclusion contributed to the continued creation of a proof of concept on using creative and cultural organizing strategies.

The film was also screened in 2021 in the St. Paul’s District at The Fuse Festival, an annual outdoor community celebration by Teens With a Purpose (TWP). Although outside of this project’s scope, showing the film at this festival is significant for Love as a community stakeholder. The festival’s inclusion is relevant because some people in St. Paul’s did not feel comfortable heading to the Attucks Theater for the live shows even though they were in their community. Love shares:

Being outdoors and in Purpose Park in the backyard, and with TWP, that’s different… [it’s] really important to me that they didn’t have to go to the Attucks, a place that they don’t even rock with or get. They can stay outside in their own community and see themselves be celebrated and be lifted up with humor.

Staying committed to communities and stakeholders who are part of culturally and creative organizing campaigns demands that organizations keep communities included in the ongoing processes every step of the way. Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave is not meant to only bring joy to communities who are the most impacted by injustices or to whoever will be reached through film distribution, but to the communities where the organizing project began and continues.

Begun in 2020, Phase Two and Three organizing and creative processes continue in parallel in 2021; they also continue to inform each other in a symbiotic relationship that necessitates fluidity, flexibility, and institutional creativity. While Phase One goals may seem more defined and connected to building movement, shifting cultures, and expanding community power, Phases Two and Three also continue to contribute to those happenings. The use of films as creative and cultural organizing tools creates endless possibilities for building movement through collective experiences and mobilizing communities to vote. Additionally, opportunities were created to shift the culture of comedy and how the climate crisis and the communities impacted are discussed, as well as to expand community power through sharing the story of Hampton Roads. Much like the successful shifting of post-production goals within creative processes, organizing processes shifted based on world and national events. Even though plans changed, successful organizing still occurred virtually.

The possibilities that are in front of HHC as organizing and creative processes continue forward are many. Underwater Projects is heading back into production in the summer of 2021, and Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave continues to be submitted to and screened at festivals. Additionally, HHC will be using Ain’t Your Mama’s Heat Wave as a critical component for organizing and mobilizing people in Virginia during the upcoming 2021 midterm elections. The exploration of Phases One through Three of the HROP demonstrates a successful proof of concept for using creative and cultural organizing to create cultural events and tools and mobilize for climate justice. The organizing and creative processes involved are layered and complex, and justice rarely comes easy, so understanding the capacities HHC had within the HROP to allow these processes to begin and continue is another essential part of the story.

Capacity is at the core of everything that’s possible, so capacity plus imagination.

Capacities are what is available to an organization or person to implement their organizing and creative visions and campaigns. Capacities of varying kinds can simultaneously be present with constraints. It is vital to understand what may impact existing capacities and then plan a strategy to maximize what one has and with whom they can partner or collaborate. Organizations are of different sizes and stages of development and thus have individual capacities and constraints. However, identifying any capacity constraints should not limit imagination but inspire the pushing of boundaries and the designing of creative solutions. Several key types of capacities have been present during the HROP, and they are explored below alongside any constraints:

Institutional capacity is a core capacity within the HROP and all other organizing and advocacy work done by Hip Hop Caucus (HHC). HHC has developed the institutional capacity to design and facilitate creative and cultural organizing campaigns; cultivate cultural and grassroots leaders; present trusted creative and cultural events; impact all public policy layers through advocacy, organizing, and mobilizing; and support other organizations through partnership and thought leadership. Muhammad offers, “The institution of the Hip Hop Caucus, which is very key, is setting a precedence of how we should look at culture, how we should use culture.” Through continually collaborating with communities and organizations and bringing on volunteers, creatives, artists, organizers, and activists as part of their staff and network, they have added to institutional knowledge and capacity.

A constraint present was having a vision that was bigger than the institutional capacity present. Havstad explains:

We executed a big vision. And it was, in reality, a vision that was bigger than our institutional capacity at the time… Not everything could happen, how we would have exactly wanted to happen… but we approached it with a make it happen type approach…But, I wouldn’t recommend doing what we did at the scale where we were at the time. I would recommend having more scale in place or scaling up to be able to do the kind of strategies at the level that we did it.

An additional constraint on institutional capacity can be human capacity. HHC navigated implementing the vision of the HROP, including the organizing, the comedy shows, and the films with the people on hand and bringing in more people as possible. People had to wear multiple hats, and this stretched the HHC team thin. Still, they were able to work through challenges by drawing on their network and collaborators to fluidly accomplish the goals created for the project when it was still an idea. The institutional capacity level did not prevent HHC from being successful, but capacities must be considered when designing an organizing project.